- Home

- Shannon Polson

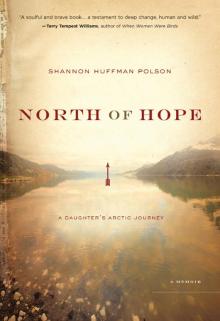

North of Hope

North of Hope Read online

SHANNON HUFFMAN POLSON

NORTH OF HOPE

A DAUGHTER’S ARCTIC JOURNEY

Map

FOR DAD AND KATHY

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law—

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed—

…

O life as futile, then, as frail!

O for thy voice to soothe and bless!

What hope of answer, or redress?

Behind the veil, behind, the veil.

—Lord Alfred Tennyson, In Memoriam

My God my grief forgive my grief tamed in language to a fear I can bear.

Make of my anguish

more than I can make. Lord, hear my prayer.

—Christian Wiman, “This Mind of Dying”

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Map

Dedication

1. A Scarred Sky

2. Restless Waters

Requiem: Kyrie

3. The Valley of the Shadow

4. Damp Shadows

5. The River within Us

6. Live Water

Requiem: Tuba Mirum

7. A Precarious Life

8. The Weight of Days

9. A Ceaseless River

Requiem: Offertorium

10. A Unique Opportunity

11. Bitter River

Requiem: Sanctus

12. Desert Springs

13. Barren Sands of a Desolate Creek

Requiem: Benedictus

14. Dies Irae

Requiem: Lacrymosa

15. Slants of Light

16. An Intentional Design

Epilogue

Afterword

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Share Your Thoughts

CHAPTER 1

A SCARRED SKY

Hold my hand in this rupture of the planet

while the scar of a purple sky becomes a star.

—Pablo Neruda, Canto General

The plane fell from the clouds toward the dirt airstrip in the Inupiat village of Kaktovik, Alaska. I braced myself against the seat in front of me. Windows aged and opaque blurred the borders of ice and land, sea and sky. The airstrip rushed upward with menacing inevitability. Kaktovik perched on Barter Island, a barrier island shaped like a bison’s skull just north of the Arctic Coastal Plain. Ice stretched from just offshore to the horizon. The Beech 1900 touched down with all the grace of a drunk, first one wheel and then the other staggering on the rough surface. Our bodies lurched forward and to the side. Gravel crunched beneath the wheels until the sound smoothed into a rhythmic bumping to the end of the runway.

As I walked off the plane down the rickety stairs, the Arctic wind cut through my fleece. I stood on the boundary between land and sea, water and ice. It was the end of the world. The ultima Thule.

As much as I pretended that courage motivated my trip, my arrival was a supplication born of a bewildering devastation I could not shake. I came on my knees, begging and desperate. Though I was reared in Alaska, this was my first trip to the Arctic. But it was not the first day of this journey. This journey began a year ago, though I didn’t then understand it, when the call came.

I was thirty-three years old, working in a new position in finance at a large company in Seattle. I didn’t like finance, though I enjoyed working with my colleagues. I was smitten with a man named Peter, whom I had met three years earlier in business school in the Northeast. He was the first person I had ever thought I might marry. And then, on June 23, 2005, sitting on the couch of my Seattle apartment on a chilly summer evening, we decided things weren’t working between us. I left early the next morning to drive to see my brother Sam and his wife in Portland, my dreams running down my face. That was Friday.

On Sunday, Sam, his wife, and I headed to the open-air market in Portland. A warm breeze wafted through the artists’ stalls, and my sister-in-law and I strolled among the booths waiting for Sam to park and join us for lunch.

My phone rang, muffled, inside my purse. We reached the end of one row of artists’ booths and turned the corner to walk down another. I fumbled around in my purse and silenced the ring, expecting to have plenty of time to talk on the three-hour drive home. From a distance, Sam ambled toward us, the same amble our dad had, all long strong legs. Walking among the artists’ offerings, the three of us decided on lunch and sat at a picnic table to eat. The late morning sun settled around our shoulders as gently as a blanket. Around us drifted the laughter of children, the smell of cinnamon sugar and honey on elephant ears, and friendly flashes of color from wandering jesters with balloons.

As we returned to our cars, the pain of my breakup two days earlier suspended briefly in the cocoon of companionship, I said goodbye to Sam and his wife. I settled into my blue Jetta, turned the key, and smiled in the rearview mirror, holding my phone on my shoulder to listen to voicemail. I turned toward the highway, where I would leave my brother and his wife behind to head north.

Then the earth trembled.

The earth erupted.

“This is Officer Holschen from Kaktovik, Alaska, calling for Shannon Huffman. Please call me as soon as you get this message.”

I didn’t know the voice. I could barely comprehend the words. I pulled over. I called Sam and told him to pull over behind me, that I had just had a strange call. He jumped from his truck and strode to the passenger’s side of my car. As he climbed into the passenger’s seat—his frame, almost as tall as Dad’s, filled it—I looked at my text messages and found a number with a 907 area code, indicating Alaska, and three additional numbers at the end: 911. My hand shook as I dialed. I couldn’t remember my hand ever having been shaky before, but I couldn’t stop the tremors.

“North Slope Borough,” said the voice on the other end of the line.

There is a time in each of our lives when we are hurled into the terrible understanding that bedrock can crumble in the blink of an eye. And still, I felt a quiet and surprising steadiness, something wrapping itself around me to shield me from things to come. The shock protects you from the horror for a while, a brief respite from the cutting pain to come, a padding of grace. Even when you think you are feeling the pain, it has yet to begin.

“This is Shannon Huffman, returning Officer Holschen’s call.”

“Are you related to Richard and Katherine Huffman?” the voice asked.

“I’m Rich’s daughter.”

“I’m sorry to tell you this,” said the voice, “but a bear came into their campsite last night …”

Every part of what I thought I knew blazed like the brightest sun, extinguishing to blackness. The earth wobbled and spun out of orbit. Gravity no longer existed.

A flash of calculation appeared in the chaos, a shard of clarity thin and brittle as a sliver of glass: I had talked to Dad and Kathy the previous Sunday on Father’s Day when they called on the satellite phone from a riverbank on the Hulahula River. They were fine, laughing, loving their trip. I would take care of them. I would need to make arrangements to get them to a hospital. I would need to talk to the doctors.

“… and they were both killed.”

Exactly at that moment, Sam whispered, “Are they dead?” I nodded, all at once unbelieving, angry at the question, unable to breathe. In one prolonged instant, I vaguely felt the weight of Sam’s head on my shoulder. I heard from him something like a sob. My breath caught in my throat. For a moment, time stood still. Cars driving by froze. People on the sidewalk halted midstep. Sounds hushed.

I

’m not sure how I closed the conversation, the first of many, with Officer Holschen, but it had something to do with having bodies sent to Anchorage. I remember asking him not to release their names until we had had a chance to inform Kathy’s family. I registered a muted note of surprise—anything I registered was muted, as though I were covered in a layer of foam—that I knew what questions to ask. The questions that were harder to ask, and impossible to answer, came later.

Now, only a year later, I arrived in the Arctic to float the Hulahula River, wishing I’d had a chance to say goodbye. Wishing I had spent more time with Dad and Kathy on rivers. Wishing for a sense of deeper connection to them. I had hoped Sam might come on this trip too, but he declined. He had immersed himself in distance cycling and had a 1200-kilometer ride scheduled while I was away on the river. Our brother Max was tied up at work in D.C. I had come feeling hollow, scooped out, empty. I had come because I knew I had to, though I couldn’t articulate why.

I’d chosen my two traveling companions for their willingness to make the trip: my adopted brother, Ned, and his work colleague Sally. We stumbled down the shaky steps from the plane onto the frozen dirt runway in the island village of Kaktovik, the only settlement on the northern edge of Alaska between the Canadian border and Barrow. Our journey would start upriver along the Hulahula River on the mainland, just as Dad and Kathy’s trip had, requiring a flight south on a yet smaller plane. But first we had to pick up our raft and other supplies.

The few other passengers from the flight to Kaktovik dispersed into the treeless landscape, and we stood alone under an overcast sky. Our loneliness was short-lived; within a few minutes of the plane’s landing, a man named Ed, wearing a large mustache and a down coat, picked us up in a school bus that had seen better days. We each took our own seat; we were the only passengers. Ned sat rigidly even as the bus bumped over one of the town’s handful of short dirt roads to the Waldo Arms Hotel, a group of derelict trailers and Quonset huts. Sally couldn’t sit still in the bus seat. She had surprised me at our first meeting. I had heard only that she also kayaked, yet she was so plump as to appear almost round, with red smiling cheeks and dark blond hair pulled back in a ponytail.

“Wow! I can’t believe we’re finally here! Never thought I’d actually be in the Arctic!” Sally said. Her grin came easily, and I swallowed against how it chafed me. We were a motley crew, the three of us, I thought. To be embarking on a journey so personally significant with someone I didn’t know seemed questionable at best.

Ned smiled something that looked more like a grimace, a second too late for spontaneity.

“Amazing,” I said. Even to me my voice sounded flat.

I figured Sally must be smart; she worked with Ned in a market research firm back East. Ned and I had never been close. Growing up, we wore on each other like grinding gears. I assumed that adulthood had tempered his youthful angst, though we had not spent any significant time together in the years intervening. I had not wanted to come alone, and yet I hoped that neither Ned nor Sally would require me to engage with them. I wanted to have my own trip.

Outside of the dirty bus windows, the tiny houses of the village decayed into the landscape, brutalized by the harsh weather. They reminded me of old ice cubes left too long in the tray, withered in the subfreezing temperatures. No trees grew this far north, so the whole of the tiny village was visible. Old snowmobiles and broken dogsleds hunched in dirt yards, protected by mangy dogs straining at their chains outside the small homes. Other dogs slunk through the streets.

The bus bumped to a halt in front of Waldo Arms, which was barely distinguishable from the buildings around it. A moose skull and antlers and a Dall sheep skull, scoured white by wind and snow, sat outside the hotel doors. Clouds clustered about the mountains to the south when we arrived, threatening our afternoon departure plans, but there was still a lot to do. We would be renting a raft from Walt Audi, who ran Waldo Arms with his wife, Merilyn. Walt had been stationed in Kaktovik years ago as part of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line set up by Eisenhower in the late 1940s as the nation’s primary air defense in case of a Russian invasion through Alaska. After that, he flew for years as one of Alaska’s original bush pilots. A pile of bent propellers next to a shed by the airstrip attested to Walt’s mythic indestructibility.

Ed worked with Walt and Merilyn. He took us through the drill of inflating the fourteen-foot blue rubber raft, checking the pressure and learning the pumps, practicing loading the raft with our enormous pile of coated nylon and rubber dry bags. As Ed gathered equipment, an Inupiat woman came to stand in the doorway and told stories of going far out onto the ice to hunt walrus. Ed pulled out a scale, and we weighed the gear, including the raft: 440 pounds. The pilot needed to know this so he could decide how many trips to make to ferry us and our gear to our put-in point. We bought white fuel for our camp stoves from Ed, disassembled the raft, and loaded the truck with our gear to go back to the airfield.

Our preparation was complete, but clouds still hung heavily over the mountains. The last weather call grounded us until the next day. Even if one could find shelter from the elements in this tiny village teetering on the edge of the world, there was never any question that nature ruled. We were forced to slow down, to take nature on her own terms. The start of our trip on the Hulahula would have to wait. We were in Kaktovik for the night.

Waldo Arms had a monopoly on lodging, and a room ran a couple of hundred dollars a night, well beyond our trip budget. We opted for the bunkhouse at forty dollars a night. Bunkhouse was a euphemistic term: behind the Quonset hut of the hotel was an uninsulated and unlit plywood shed with filthy mattresses piled on top of each other on rudimentary bunks. A narrow gangplank connected the bunkhouse to the rest of the Waldo Arms trailers. Ragged Visqueen covering the broken glass of a window let in some light.

“Well, it’s probably too cold for bugs,” I said to no one in particular.

“Hope so,” said Sally, maintaining what I thought was remarkable composure for an East Coast city girl in a remote Alaskan village. She began arranging her gear.

Dropping my backpack and sleeping bag on one of the bare mattresses, I walked up the gangplank and headed into the common area of Waldo Arms. Inside, I sank into an ancient gold floral velvet couch and took in the room around me. The couch sat on a rust-colored carpet well scuffed by boots over the years. A large piece of scrimshawed baleen hung on the wall above a notice of the musk ox hunt, warnings about polar bears roaming the village, maps of Alaska, and assorted articles and calendars about Alaska and the Arctic from past decades. Static and the occasional voice scratched an uneven staccato over the radio in the office at the far end of the room. A small window into the kitchen with a laminated menu beside it offered expensive greasy food, and a couple of picnic tables covered in red-and-white-checkered vinyl tablecloths sat in the dining area. In the kitchen, the gentle cacophony of clanging pans was strangely soothing in its familiarity. As my body relaxed into the couch, all of the details that had insulated me for so long—the decision to come, organizing the trip, the preparation before departure which had filled the time and the crevices of my mind—evaporated like the Arctic coastal fog in the summer midnight sun. Now my mind focused with a clarity that, while not welcome, was inevitable.

On June 14, 2005, a little over a year ago, I had received the last email I would ever see from Dad:

Hi all. I know you don’t need all this but here it is: we leave on the 15th on Frontier Flying service to Barter Island. If the weather is good, we fly the same day to Grasser’s on the Hulahula River. We have a good orange tent, two inflatables (red and yellow), extra paddles, food for 17 days, first aid stuff, dry suits, helmets, pfds, sat phone, gps and vhf radio. We plan to take two weeks goofing off and paddling down river for a pickup at the coast on the 29th and fly back to Fairbanks that night. Then to cabin for a couple of days. We fly from the village of Kaktovik on Barter Island with Alaska Flyers. Their phone is 907-640-6324—owner is Walt and pil

ot is Tom. The satellite phone is with Iridium through Surveyor’s exchange at 561-6501. You guys be safe and well. I love you and I am very proud of each of you! Kathy sends her best! love, Dad

I hadn’t noticed the detail they’d given. Details we would need to look for them, to identify a campsite. Last year they had been in this same place, excited, preparing, checking equipment. Perhaps they had sat on the same couch.

The possibilities and wonderings pressed in, soft and firm like chloroform; I needed to move. Ned and Sally stayed behind to read, but I needed the feel of ground beneath my boots. I zipped up my coat and headed through the set of double doors. Outside, a barbed wind scratched at my face and penetrated my fleece. I welcomed the distraction. I headed toward the police station.

Though most of the scattered buildings of the village cowered from the ferocity of Arctic weather, the government buildings, funded by oil companies, stood solidly. At the police station, I walked into the welcome of a well-lit room, entering the concrete edge of the story I had been sketching for a year. Officer Holschen, the policeman who had first called me, had fielded my calls many times in the intervening months, rehashing details and events.

“Where exactly were they on the beach?”

“How do you know how long they had been dead?”

“Have you seen bears act this way with other people?”

“Can you tell exactly what killed them?”

“Where was the emergency locater beacon? Had they tried to use it?”

A thousand other questions had burped rudely into my mind, never at opportune moments. Each time, I called Officer Holschen, and each time, he answered patiently, talked through my questions, never impatient, never annoyed. His life and line of work had taught him to understand the survivor’s need to pick up each rock and turn it over again and again and again. He understood the human delusion that believes that if we can answer questions, fill in the story, somehow we might turn back the clock.

North of Hope

North of Hope