- Home

- Shannon Polson

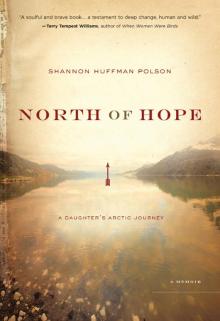

North of Hope Page 5

North of Hope Read online

Page 5

I depended on knowing. I knew facts. Facts were clean. They were neat and orderly, like the facts I’d researched and put on three-by-five cards when I debated in high school. Facts I could reference to prove a point, win an argument. I read about these bears the year after Dad and Kathy died. I continued to read about them. I knew them from the newspaper’s picture of that seven-year-old, healthy grizzly on the north end of that Arctic beach, the remnants of the wrecked campsite just to the south.

Barren-ground grizzlies are smaller and more aggressive than their southern counterparts. Food on the Arctic tundra is scarce, and grizzlies, the brown bear with the least-dense population and the lowest reproductive rate, cover hundreds of square miles of territory to feed themselves and maintain their population. The barren-ground grizzly in the photo killed my father and stepmother. These were not clean facts. They dripped with gore.

The timbre of the Arctic’s music changed. Red tooth and claw bristled on the clean lines of landscape. I knew the bears moved toward the river on the coastal plain where we would be in another week. Logically, they would have moved a distance away by the time we reached that point. And yet the existence of the grizzlies affirmed my entry into wilderness in the same inexplicable sense as seeing the polar bear in Kaktovik did; a surprising solace rested comfortably next to my abhorrence and just punctured the aridity of my spirit.

A memory: “If I die tomorrow,” said Dad, many times, “I want you to remember that no matter how much money you make, you save at least ten percent of it, more if you can.” That’s not all I want to remember, Dad. But I remember. Ten percent.

Looking down to the coastal plain from the Cessna, I felt momentarily protected, and yet uncomfortably separate, from the wild world below. I was cocooned in the limits of my understanding, trying to squirm through what bound me, though my wings were yet unformed. I considered that when Faulkner’s Ike went into the wild to see Old Ben, he left his weapon behind. Even that was not enough. He hung his compass and his watch on a tree. He left the trappings and security of his world behind to join the concert of wildness. I could not hang up my compass yet. “Be scared. You can’t help that,” Ike’s mentor, Sam Fathers, said. “But don’t be afraid.” I was scared. And I was still afraid.

Along the west side of the river, we flew over two Inupiat fishing camps, shacks falling apart and old oil barrels askew on the tundra.

“See that hole?” Tom pointed out a gaping blackness in the side of one of the shacks. “That’s where a grizzly forced its way in.” I stared at the grotesque collision of ancient wisdom and ways of life, the violence of the wild, the violence of modernity, until it fell behind the plane’s progress. Continuing south, the green coastal plain grew into foothills and the river disappeared into small canyons. Held in by the high and narrow banks, the river leapt and churned.

“Those are the rapids?” I asked Tom through the headset. “They don’t look too bad.”

“They’re not—from up here,” he said, smiling.

A memory: running with Dad over his lunchtimes the summer I was ten years old and entering my first 10k races with him. “See that guy ahead of you in the red shorts?” Dad asked, as we started up a hill. “He’s slowing down where it gets steep. Let’s pass him!”

Despite my Alaskan upbringing, I’d never seen this landscape over which we flew, a landscape unknown even to most Alaskans because of its inaccessibility. Westerners are new to this land, but people have lived in the northernmost reaches of Alaska for more than ten thousand years. The Inupiat populate the coastal areas. The Gwich’in Indians live south of the Brooks Range in a region stretching from central Alaska into Canada. Both depend on the land and the sea to sustain their communities, even today. For the Gwich’in, reliant on the Porcupine Caribou Herd, the Arctic Coastal Plain is known as “the place where life begins” and as “the sacred calving grounds.” Neither people is constrained by state or country borders, a reminder that the wilderness is bigger than any more recent attempts to define it.

Russians and Europeans were the first Westerners to explore Arctic Alaska, beginning with Captain Cook mapping its coastline in 1778. The search for the Northwest Passage brought back news of whales, beginning decades of aggressive whale hunting. Most whaling expeditions lasted two years, sailing around the coast of South America, whaling and offloading the oil and baleen in the Hawaiian Islands (and frequently picking up Hawaiians to help crew), then continuing north to the Arctic until winter forced the ships south again.

The name Hulahula is first noted in correspondence between S. J. Marsh, a prospector at the turn of the twentieth century, and Alfred H. Brooks, chief geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey in the same period in a paper dated 1919. The river was referred to as “Hoolahoola,” a word of Kanaka, or Hawaiian, origin, meaning “the dance.” The paper notes that there was no ancient name for the river, and that “Hoolahoola” was bestowed in the past twenty years (since 1900) after natives of Herschel Island, a tiny island in the Beaufort Sea just off the coast of Canada’s Yukon Territory, killed a number of caribou and celebrated with a dance by the river. It is not known how the name was given or why a name of Hawaiian origin was chosen. Perhaps a crew member from the islands suggested it. But the name stuck. The dance. A celebration.

Whaling continued until several factors brought it to a halt, among which were the last shots of the Civil War, fired by the Confederate ship Shenandoah in the Bering Strait on June 22, 1865. Though it was two months after Lee’s surrender, the Shenandoah hadn’t got the word. It burned twenty-one Arctic whalers in this two-month period, decimating the whaling fleet. The Shenandoah learned the war was over in August when it arrived on the California coast. Whaling gave way to walrus hunting, which continued until restrictions were imposed in the midtwentieth century.

The Cold War military buildup increased the number of visitors to the Arctic, along with the establishment of the Distant Early Warning Line, a series of communications stations intended to provide warning of Soviet attack. The subsequent discovery of oil led to increased development and debate, with worldwide interest from oil companies looking for extraction opportunities and environmentalists defending the uniqueness and fragility of the Arctic ecosystem.

Both Dad and Kathy had been in Alaska since the late 1960s. Today’s literature describes the experience of that decade with talk of protests, drugs, and sex, but Dad felt a sense of honor in entering the army on the draft after completing law school. He trained as an enlisted combat engineer before realizing that his law degree allowed him the opportunity for service as an army attorney in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. Though initially he was slated for Vietnam, the army sent him to Alaska, flying him around the state executing wills and powers of attorney and prosecuting the myriad drug cases defining military JAG at the time. When his military commitment ended, a year after I was born, he worked in Anchorage for the city attorney’s office and then opened a private practice. He fell in love with the land and, for as long as I can remember, pulled us along with him on backpacking trips in the Chugach Mountains, and even on a few easy river trips by canoe.

Kathy came to Alaska after a construction job in West Africa. Her adventurous spirit was unquenched by her sorority days at Depauw and a subsequent master’s in education at the University of Texas. She brought her bright blue eyes and full, sweet laugh to Denali National Park to work as a naturalist when the roads were still closed all winter and only a weekly train brought supplies or the opportunity to head into town. She was one of those women a lot of men are secretly in love with. Kathy taught at Tri-Valley Elementary School a few miles north of Denali fall through spring. She traveled with her first husband, a wildlife photographer, by foot and folding kayak around the interior of Alaska. After their divorce, she taught in Anchorage, settling into a city routine. She and Dad married with the agreement that he would learn to dance and she would learn to ski. They compromised by doing neither. Still, when Dad started turning more attention to t

he outdoors after years of office sequestration, it was not a new experience for her.

They began longer river trips in the late 1990s. Their river journal from 1999 begins with a recipe for raisin muffins, and then: “Banks of the Yukon. Just entering dozen islands.” One journal records trips on the Tanana in 1999, the Charley River in 2000, Harriman Fjord in 2000, and the Gulkana River in 2001. Dad’s enthusiasm was initially too much; on the trip down the Charley River in the interior of Alaska, Kathy’s kayak flipped, and her head—luckily helmeted—hit a rock. They pulled over. She was spooked and angry. One day into the trip, they made camp on a gravel bar, which was as far as they traveled. They contacted the one plane flying over their area each day with their VHF radio and arranged for an early pickup.

Dad learned from that experience. After a safe return, they took two trips to the weeklong Otter Bar Kayak School in California, spent evenings on rivers at home, and built back up to remote passages. Kathy was less interested in whitewater than she was in time with her husband, so Dad was happy to hike back and paddle her boat through areas where she was uncomfortable. They kayaked the Canning River on the far west boundary of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 2004. The Hulahula River is the next navigable drainage to the east. I imagine Dad had in mind traveling each of the rivers in the refuge in the same way he had read his way chronologically through American literature, starting with the sermons of Cotton Mather. Once the magic of the Arctic worked its way under his skin, it became a part of him, that much I knew.

Now I embarked to find my father, to know him, having realized, once he was gone, how little I knew of him, unwilling to accept that what I knew of my father was all I would have a chance to know. I hoped for just a glimpse of some of the magic I knew he and Kathy had experienced on this trip. Throughout humankind’s long history, the idea of journey has carried with it expectations of adventure, of wildlife, of challenge, of conquest. I was scared to have any expectations, no longer knowing how to consider this thing called life after the past summer. I stared out of the Cessna’s windows. Farther upriver, thin blue and white lines of aufeis began to define the riverbanks of the river valley.

Aufeis was one thing I had been concerned about on the river. It forms in winter months, when water flowing in a deeper channel of the river is dammed by an ice jam downriver in a shallower channel. The water continues to flow beneath the dam, but also overflows it, spreads out over the banks, and freezes. This cycle of overflowing and freezing happens many times, until the ice forms up to three meters deep. Until the spring melt, this thick ice stretches across the river, but water still flows beneath it, and the current can sweep boats beneath the ice, resulting in capsizing and drowning. This year, the aufeis had melted from the channel. It didn’t look like we would have a problem.

The greatest danger I felt then, and sometimes still feel, is of losing the memories.

When Dad and Kathy had flown in last year, it had been colder, with aufeis choking the river. They were excited to be heading back into the wilderness. Later, Tom told reporters that Kathy had questioned him thoroughly about emergency procedures. I remembered reading the newspaper article. I remembered walking into the silent house. I remembered dinner at Sostanza in Seattle with them both, the fireplace warming the room. I remembered so much, and so little. Time’s linearity evaporated as we flew against the river’s current below. Was I trespassing too much among the bones of the dead? Qarrtsiluni. Have mercy.

Foothills drawn in the muted browns, greens, and ochre of sandstone and limestone grew into the heights of the Romanzof Mountains, and the glacial peaks of Michelson and Chamberlin soared to either side. Valleys leading back into mountains beckoned me. Farther south, the river spread out again as the valley widened, no longer confined to the canyons. The sweep of land appeared more desolate than life-giving. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” What was I thinking? This couldn’t be a good idea.

A tundra airstrip came into focus on the west side of the river—Grasser’s, one of the more established landing areas in the Arctic, named for Marlin Grasser, who spent time on the Hulahula River in the mid- and late-twentieth century, guiding sheep hunters. Tom flew over, banked for a steep approach, and landed the airplane. He killed the engine. We jumped out. Ned and Sally had been standing at the edge of the airstrip; now they joined us, and the four of us rapidly unloaded the remaining bags from the back of the plane.

There is a saying in Alaska that three things kill small-plane pilots: weather, weather, and weather. With clouds likely to close in, Tom wasn’t taking any chances. By the time we pulled the gear to the side of the landing strip, he had cranked the propeller and maneuvered the 206 for takeoff. With a burst of noise, the Cessna rolled down the strip on fat tundra tires, and wings grabbed air. The buzz of the plane dissolved to the north. Except for a light breeze, it was quiet.

CHAPTER 6

LIVE WATER

Live water heals memories.

—Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Ned and Sally had already sorted the gear and inflated the large blue raft by the time I arrived. Mountains of limestone, sandstone, and shale framed our embarkation point, ancient rocks deposited by ancient seas forced upward by the pressure of the Pacific Plate far to the south. These mountains were the second range pushed up by tectonic forces; the first range had eroded away, and the newer mountains continue to reach skyward even today. The sprawling scape was a picture of the oldest forces of creation, a valley carved by glacier, water, and wind, the rise and fall of oceans, the shaping of a world long before our time.

Relative to the geologic context, the pile of gear that had seemed so immense as we loaded the Cessna shrank, along with us, to insignificance. We had departed with much, but it was contained for river travel in bear-proof food canisters and waterproof dry bags we had packed before leaving for the airplane. Before the trip, the food we needed for ten days had spread out to cover the floor and furniture of the living room in the Denali cabin from which we had launched our expedition. I had counted out packets of oatmeal, candy bars, energy bars, dehydrated food. With permanent marker and duct tape, we had labeled the bear canisters with the number of days worth of meals they contained.

We didn’t talk about the other load, the one there was no manual for securing. Memories, fear, horror, determination, unworthiness, emptiness. I didn’t begin to know how to secure these things, or how to let them go.

“You guys ready for this?” Sally asked.

“Sure.” I smiled.

How would I survive this?

Ned started cinching down straps on each side of the boat. He seemed to measure the strap tension with his eyes, repositioning dry bags as needed, yanking on the ends of the straps until they were tight enough to strain against the rough rope running around the top of the raft.

“What about you?” I asked.

“Heck yeah!” Sally said. “This is going to be great!”

“We got a nice day to start, at least,” I said, trying to swallow my unease.

The two guns were also in dry bags. I was uncomfortable with their positioning. Eight years of military training had drilled into me the importance of safety; barrels of loaded weapons are always pointed up and away from people, but cramming them in a raft didn’t permit the same level of discipline. Despite our best efforts, our discipline was far from military.

We finished packing the raft. Each dry bag had its place, and canvas compression straps secured the load onto the fourteen-foot blue rubber craft. Ned tightened each strap one final time with easy confidence and a force approaching viciousness. The side of the raft read NRS, the brand; I thought for this journey she should have a name. Hope, perhaps. Or Desperation. Longing, maybe. Prayer, even better. Or Stupidity. I tried to put these thoughts out of my mind. I clipped my daypack close to me with a carabiner on a compression strap, being careful not to let my most precious cargo—the small plastic bottle and the plastic bag I had transported

carefully from Seattle, along with a tiny silver amulet from Father Jack in Healy—be crushed by other gear or the boat.

Kathy’s journal entry on their first day was this:

6-15-05 7:08 PM … Beautiful flight up river and landed at gravel bar airstrip. Within 2 hours saw a wolf and about 20 dall sheep, ewes and lambs…. there’s a strong wind from the north which makes for lots of layers of clothing. But the sun is shining and … we are thrilled to be back in God’s country again! Keep us safe, Lord. Kathy

“Let’s get this in the water,” Ned said. “Can you each grab a side?” Sally and I took positions on either side and grabbed the rope. “One, two, pull!” Ned said. The raft followed us reluctantly to rest on the water.

Dad and Kathy had pitched a tent at Grasser’s and stayed to relax and hike for a day, but we wanted to get some water under us, to accept the river’s invitation, to move forward. The sun glanced off the surface of the water, and a light breeze cooled our skin. I inhaled deeply, and exhaled, slowly. We were doing it. After the frigidity of the coast, I relaxed into the warmth of the sun.

I sat on the port side of the raft, feigning confidence, worried that our steed would feel my inexperience, sense my trepidation. But if she did, she didn’t show it. My seat felt secure, and my paddle strokes against the water smooth. It occurred to me I wanted too much from this trip. For those of us who spend less time in wild places than we do in cities, it’s easy to arrive with urban expectations, with checklists of hopes and desires. This is the wrong way to come into a wilderness bigger than any of the demands that can be made of it. Lessons and healing come only through an open spirit and uncluttered mind. I felt poorly positioned for success.

Though VHF and UHF radios and a satellite phone stayed handy in waterproof bags, we couldn’t have been farther from any reality outside of wilderness. With the exception of a handful of other adventurers making their way on this or other Arctic rivers and the three hundred people in the village of Kaktovik, there were no other people within hundreds of square miles. Despite the relative explosion in adventure travel and ecotourism, not to mention continued hunting in the Arctic, only a few hundred people visit the Arctic Refuge each year.

North of Hope

North of Hope